Teaser 2474: [Flipping counters]

From The Sunday Times, 21st February 2010 [link]

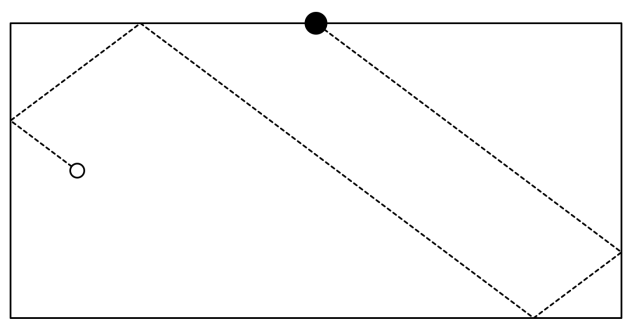

Imagine that you have 64 small round counters, black on one side and white on the other, and you have to place them all on the different squares of a chessboard, so that those on the black squares all finish white side up and those on the white squares finish black side up.

Note that as each counter is placed on the chessboard, you must turn over any counters already on the two, three or four adjacent squares.

In completing this task, how many times would you turn counters over?

This puzzle was originally published with no title.

[teaser2474]

Jim Randell 9:10 am on 28 November 2025 Permalink |

(See also: Enigma 1256, Enigma 1767, both also set by Bob Walker).

For an N×M array, counters will be turned over N×(M − 1) + M×(N − 1) times. In this case N = M = 8.

Solution: 112 counters are turned over.

We can use the code from Enigma 1767 to generate a sequence of moves for an 8×8 grid:

At the end of this procedure each counter is placed, and then turned over 0 or 2 times. So when we first place a counter we do so with the desired final face uppermost.

LikeLike